The Crime

On Tuesday, June 20, 1893, a man walked into the Balm Post Office, approached postmistress Betty Harris, and requested to send $5 in a registered letter to C.E. Bryan of Remlap. The man, who identified himself as H.B. Smith, presented $5 in coins and asked Harris to exchange it for $5 in bills. Harris accepted the request, enclosed the money in an envelope, and mailed it to Bryan in Remlap.

Smith then requested to buy some stamps and offered a silver dollar as payment. Harris, taking the coin, noticed that it was worn and refused to accept it as payment. Smith soon left, and it was discovered that the $5 he provided in exchange for bills was counterfeit.

Balm

Balm was a rural hub established after the Civil War. While Balm proper referred to the area around Pine Grove Church, the name could also pertain to all of Blount County Beat 28, also known as Thompson’s Beat. The July 1883 edition of Bradstreet’s Book of Commercial Ratings lists Balm as having a population of 58.[1] Census, property, and tax records dispute this number regarding the hamlet of Balm. However, Balm appeared at a time when populations shifted. At its height, it compromised the church, adjoining school, and post office.

Since Bradstreet’s commercial ratings refer to Balm as the greater part of Beat 28, it is difficult to determine what businesses were in Balm proper. J.A. Freeman, E.C. Bynum, S.D. Smith, and P.D. Bullard are all listed as business owners, while the Southern Democrat mentions B.Q. Evans who moved from Balm to Oneonta to practice law.[2]

In many ways Balm was a precursor to Altoona, which also meant that the rise of Altoona meant the end of Balm. Several prominent families, including those who were associated with business or the post office in Balm, made their way to Altoona and played an influential role in founding the town. Balm last appeared on a Bradstreet report in September 1903, while the post office was dissolved on April 4, 1904.[3]

Betty Harris

Betty Harris became postmaster at Balm on May 14, 1886, and served until February 4, 1895.[4] Born Elizabeth Amelia Davis on July 25, 1858, she was the daughter of John E. and Elizabeth McMath Davis.[5] Betty’s background and formative years are unknown. While her Find-A-Grave page states she was born in Jefferson County, there is no other documentation to support this. In fact, the names of her parents are only found on her headstone. Although several Davis families lived in Blount County, research has found no connection between them and John E. Davis.

Betty married to John Cobb Harris, Sr. on September 26, 1875.[6] The marriage took place in Etowah County at Betty’s residence. Interestingly, this detail along with the fact that her consent for marriage was given by a William Abbot reveals that Betty was separated from her parents. This is potentially explained by a news article from 1881, which states that John E. was a resident of Chilton County.[7]

With questions regarding Betty’s formative years, her connection and eventual marriage to Harris also remains a mystery. Her appearance in Etowah County records might suggest a connection to the William Joseph Harris family of Moody’s Chapel.[8] However, Cobb Harris was from a different group altogether. W.J. Harris hailed from North Carolina, while Cobb’s father, Jame Harris, came to Murphrees Valley from South Carolina.[9] While the two families may have been distantly related, they settled in two very distinct areas in Blount and Etowah Counties.

A year after marriage, the couple welcomed their first son Luther Harris.[10] This birth was followed by eight more children, five boys and four girls. It’s unknown where the Harris’ resided after marriage as a search of property records did not reveal any property ownership until a decade later. However, that transaction may provide some insight in the family’s living situation. A deed dated November 16, 1885, reveals a property transaction between the heirs of James Harris to J. Cobb Harris.[11] James Harris, the father of J. Cobb passed away before 1877.[12] It appears that J. Cobb and family resided on this portion of his father’s property until the other heirs deeded it to Cobb outright in 1886. Whatever the case may be, Harris and family did not reside in Balm until December 1880.[13]

This property encompasses both sides of County Road 39 (Murphrees Valley Road) on the east side of the Ragsdale Road/Douglas Lane Intersection. In fact, the barn visible in the pasture on the north side of the intersection is built next to the Harris Family Cemetery. It’s unknown where the actual house stood, but it’s likely that it was located on the southeast corner of the intersection, across the road from the present barn. The location of the house is important, as during Betty Harris’s tenure as postmaster, the office was probably located within her home. This was the case with most rural hub offices, including another local office Nix, in what is today known as Moody’s Chapel.

Outside of the farm, both Betty and Cobb lived rather ordinary lives. There are no records indicating any kind of business interests, and for all intents Cobb was a very successful farmer. He briefly made news when he attempted a run for Blount County Sheriff in 1892.[14] Although he lost the race, he was described as well-known and possessing all the qualities needed to make a good sheriff. Harris hailed from a wealthy and successful family, and it appears he continued to build personal wealth of his own.

Betty’s February 1895 resignation as postmaster was due to an even larger event. Relocation to Texas. On February 16, 1895, Cobb sold his Balm property to his brother William Abraham Harris.[15] This was followed by a statement in the Blount County News-Dispatch on March 14, announcing the family’s intention to move to Texas.[16] Both Betty and Cobb remained in Texas for the remainder of their lives. Cobb Harris passed away and was buried in Cleburne Memorial Cemetery on April 26, 1935.[17] Berry Harris survived him by two months, with her date of death on May 6, 1935. She was laid to rest next to her husband.

The Chase, Capture and Identity of H.B. Smith

Soon after the discovery of the counterfeit coins, Betty Harris notified her husband, Cobb Harris, who was working on the farm.[18] Determined to capture Smith, Harris and J.M. Freeman set out in hot pursuit. At this point, the story diverges. Local Blount County accounts refer to Harris and Freeman’s capture of Smith, while Birmingham papers (which were reported statewide) told a more complete story omitting Harris and Freeman and introducing federal authorities into the chase and capture of Smith.

Blount County News-Dispatch: The initial report of the counterfeit coins and initial chase by Cobb Harris and James Freeman came via W.A. Harris’s visit to the News-Dispatch office on Tuesday afternoon, just hours after the incident. Since the News-Dispatch was a weekly paper, readers would have to wait to receive the rest of the story. Unfortunately, the June 29 issue does not record a source. However, it tells that Smith was captured the day after the incident (June 21) by Harris and Freeman. After retelling the crime the article states that his capture came on June 22, two days after the incident. Smith was captured in Remlap, where it was revealed that his real name was C.E. Bryan. Harris and Freeman took Bryan by train to Birmingham. Once in the city, U.S. Commissioner Hunter placed him in jail with a $500 bond.

Montgomery Weekly Advertiser: The advertiser’s report, gleaned from an unnamed Birmingham paper stated that Betty Harris, soon after noticing the counterfeit coins notified federal authorities who set out to capture Smith. It was at that point that it was not Smith’s first visit to the Balm Post Office. He had made several previous visits as Smith, each time mailing registered letters to C.E. Bryan of Remlap, as well as other places in Blount County.

Meanwhile, a federal officer was sent to Remlap to intercept Bryan when he came to retrieve the letter mailed by Smith. However, it soon became evident that H.B. Smith and C.E. Bryan were one and the same, with Bryan using the assumed name of H.B. Smith at the Balm post office. To make matters worse, Bryan appeared to be tipped off that his game was up, as he never showed up to retrieve the money. A search was conducted, and Bryan was later surrounded in the mountains. Despite this, he was able to make an escape, only to be captured by J.A. McClellan three-quarters of a mile from Balm on the evening of June 21.

Reading between the lines of both stories reveals that the truth is most likely found in a combination of both accounts. Since the coins were counterfeit, the federal authorities were most likely called during the time or just after Harris and Freeman became involved. It was the federal agent who likely interviewed Harris and found out that Bryan had made several visits to Balm Post Office, while agents also went to Remlap to intercept both the mail and Bryan, in the process coming to realize Smith was an alias for Bryan. Meanwhile, Harris and Freeman were or were among the group that surrounded Bryan and later captured him the following evening outside of Balm.

At the time of his arrest, Bryan stated his true name, and two other counterfeit coins were found on him. The reports described him as a mountaineer, and someone who was relatively unknown. He was said to be a young man, employed by the “Government works” on the Tennessee river in Marshall County and seemed to have used Blount County as a place for conducting his counterfeit operations. However, the Blount County News-Dispatch reported that he resided near Remlap where he was employed as a section hand.[19]

C.E. Bryan

Charles E. Bryan was born in July 1867 in Marshall County, Alabama.[20] He was the son of Ashley Bryan (1812-1888) and he was the third oldest of at least four children. Bryan’s mother, Francis J. Bryan was born around 1832 and passed away between 1870 and 1873.[21] However, his father quickly remarried to Judith Antoinette Scroggins (1850-1929), a union that bore three additional children.[22]

Census records indicate that the Bryan family was not as well off as their neighbors. In the 1870 Census Ashely is shown as being a farmer with a real estate value of $50 and a personal estate valued at $250. This is in comparison to his immediate neighbors, who had real estate valued at $4,000 and $1,500 with personal estates of $1,800 and $600. Bryan’s low real estate value indicates that he may have been a sharecropper. There are also indications that Bryan may not have been able to read or write, as he signed his marriage certificate with an X mark.

By 1880, the Bryan family had relocated to Etowah County. While the 1880 census does not record estate values or property ownership, the Bryans resided in Hopper’s Precinct or what is today known as Samuel’s Chapel.[23] At first glance, it appears that the family may have continued as sharecroppers under the Hopper family. Charles, listed at 12 years old is shown as working as a farmer with his father. The census taker also recorded that Charles had attended school within the past year, but he was still unable to read or write. Interestingly, this is not the case with Ashley, who is listed as literate.

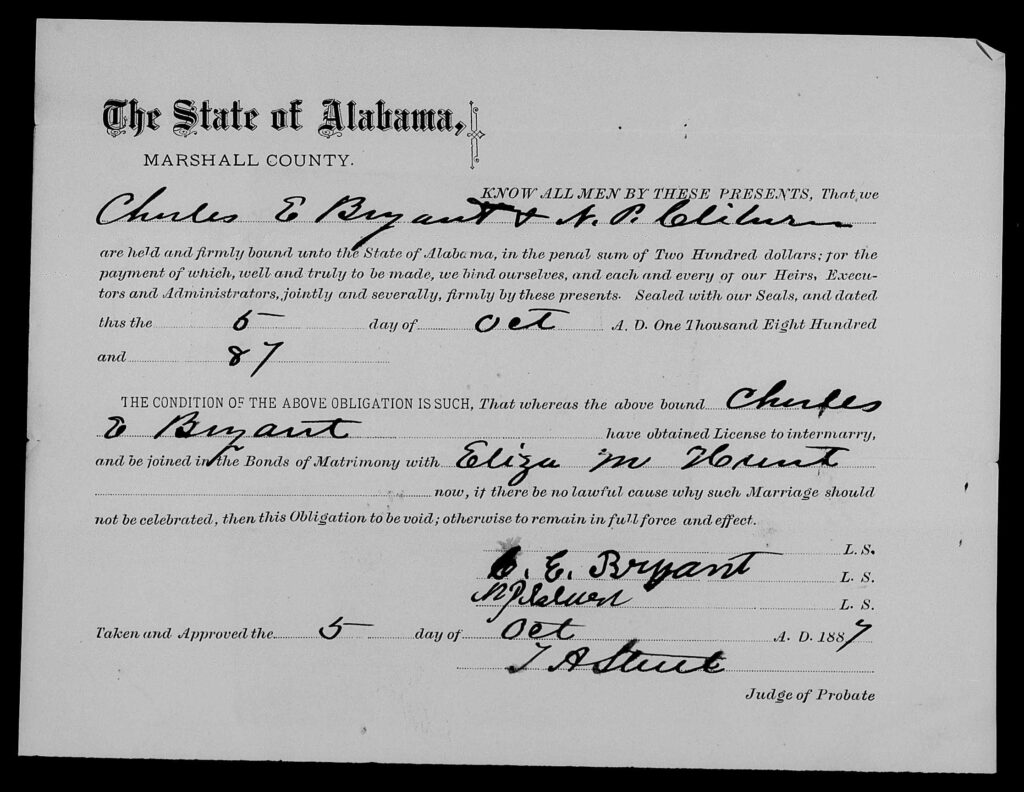

On October 5, 1887, Charles Bryan was wed to Elizabeth Mandy Hunt.[24] The ceremony took place in Marshall County, at the residence George Hunt, Elizabeth’s father. Ashely Bryan signed the letter authorizing his son to wed Hunt with an X, further indicating his illiteracy. After marriage, the couple began a family with son Oscar Bryan born in 1891. His birth was followed by daughter Annie in 1892, Lucy in 1896, Alonzo in 1898, Josie in 1901, and Esther in 1905.[25]

Confession and Trial

Through 1892 and 1893, Blount, Etowah, and Marshall Counties were flooded with counterfeit coinage. Officials believed the sudden appearance of so much counterfeit coinage was due to the work of an organized gang. Initially, it was thought that Bryan was a member of this gang. However, during his confession, Bryan claimed the coinage came from a friend in Marshall County. Bryan gave his friend one dollar for every two dollars in counterfeit coins.

Postal Inspector Mayer viewed the two coins that were found on Bryan during his capture, describing them as the “best he has ever seen in the state, and as good as he has ever seen anywhere.” He continued to describe the coins as being made of a combination of glass solution and platinum. The glass gave the coins the distinctive silver coin ring, while the platinum added a bright gloss to the face. Despite all their excellent qualities, he added that it lacked the weight of a genuine silver coin.

Bryan went before the federal grand jury in Birmingham in September 1893, where he entered a plea of guilty.[26] It’s assumed that he remained in jail during this time, as there was no other article or record between his arrest and appearance in court. His guilty plea apparently caused a case of mistaken identity, as both the Birmingham News and Birmingham Post-Herald issued announcements stating that Birmingham contractor C.E. Bryan was a different person from the one who was convicted.[27]

On September 30, 1893, Bryan was sentenced to two years of hard labor and $100 in court costs.[28] On October 31, 1893, Bryan along with seven other prisoners boarded a train for Brooklyn, New York.[29] Once there, Bryan served his time as King’s County Penitentiary. Interestingly, one of seven other men on the train was former Walnut Grove Postmaster Pinkney A. Ensley, who was sentenced to one year and a day for mishandling a large amount of postal service funds.

Later life of C.E. Bryan

It’s not recorded whether Bryan served his full sentence or what his homecoming was like. In fact, other than the 1900 census, he falls into relative obscurity. Charles, now reunited with his family, is found on the 1900 census living in Chandler, Etowah County.[30] His occupation is listed as a farmer, and he owned his home and farm. By all appearances, he resumed his life after prison, rejoining his family and becoming a property owner. Unfortunately, Bryan’s life was cut short. For reasons unknown, he passed away in 1904. He was laid to rest in Friendship Baptist Church Cemetery near Boaz. His simple in-ground headstone, of modern design reads, “Charlie Bryan 1870-1904”.

After the death of her husband, Elizabeth Bryan began to go by Mandy. She is found on the 1910 census as a widow, still residing in Chandler, Etowah County.[31] Her home was rented, and as the only working member of her family, she was listed as a laborer on a farm. As her family grew, she remained in Chandler through 1920, residing on Walls Chappell Road and continuing to work on a farm.[32] In 1930, she resided in the household of her daughter Esther Bryan Hall, who lived in Hoppers, the same area her husband was enumerated in during the 1880 census.[33]

Elizabeth Bryan passed away on December 10, 1935. She was laid to rest next to her husband in Friendship Baptist Church Cemetery. Like her husband she has a plain, modern-style, in-ground monument. However, her plot also features a hand-carved cinder block bearing the inscription Mandy Bryan. Several other members of her husband’s family are also buried in this cemetery.

[1] Bradstreet’s Book of Commercial Ratings, July 1883, Vol. 62, part 1.

[2] 20 January 1881, Southern Democrat, P.3.

[3] Dun and Bradstreet Reference Book, September 1903, Vol. 142, part 1. “Postmasters By Location,” Volume 66, Alabama, Blount County.

[4] Ibid. #3

[5] Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/104008286/elizabeth_amelia-harris: accessed August 4, 2024), memorial page for Elizabeth Amelia “Betty” Davis Harris (21 Jul 1858–6 May 1935), Find a Grave Memorial ID 104008286, citing Cleburne Memorial Cemetery, Cleburne, Johnson County, Texas, USA; Maintained by ᕚ( ςђгเร єครɭєץ )ᕘ (contributor 47918260).

[6] Etowah County Marriage Record Book A, Page 224.

[7] 4 August 1881, Blount County News-Dispatch, P.4.

[8] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/31307332/william-joseph-harris

[9] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/124651155/james_harris

[10] John Cobb Harris Senior, Kelly Family Tree, https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/157021485/person/432122402723/facts

[11] James Harris Estate to J Cobb Harris Blount County Deed Book 1-412

[12] Ephraim Harris to William A. Harris, Blount County Deed Book T, Page 333.

[13] “Home Personals,” 30 December 1880, Blount County News-Dispatch, P.1.

[14] 21 January 1892, Blount County News-Dispatch, P.3.

[15] Cobb Harris to William A. Harris Blount County Deed Book 7 Page 254.

[16] “Personal Mention,” 14 March 1895, Blount County News-Dispatch, P.3.

[17] Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/104008203/john_cobb-harris: accessed August 7, 2024), memorial page for John Cobb Harris Sr. (3 Feb 1852–26 Apr 1935), Find a Grave Memorial ID 104008203, citing Cleburne Memorial Cemetery, Cleburne, Johnson County, Texas, USA; Maintained by ᕚ( ςђгเร єครɭєץ )ᕘ (contributor 47918260).

[18] 29 June 1893, Blount County News-Dispatch, P.3.

[19] Ibid. #16

[20] Charles E. Bryan, Brenda Mason Family Tree, https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/51972414/person/242556881257/facts?_phsrc=Ykd1&_phstart=successSource

[21] Year: 1870; Census Place: Subdivision 45, Marshall, Alabama; Roll: M593_29; Page: 162A

[22] Find a Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/10938373/judith_antoinette-bryan: accessed August 7, 2024), memorial page for Judith Antoinette Scroggins Bryan (9 May 1850–26 Nov 1929), Find a Grave Memorial ID 10938373, citing Ables Springs Cemetery, Kaufman County, Texas, USA; Maintained by melanie coody (contributor 48082002). Marshall County Marriage Record, Ashley Bryan and Judith Scoggins, May 11, 1879.

[23] Year: 1880; Census Place: Etowah, Alabama; Roll: 13; Page: 340b; Enumeration District: 068

[24] “Marshall, Alabama, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-L15J-TL3?view=explore : Aug 8, 2024), image 1374 of 1707; Alabama. County Court (Marshall County).

[25] Names and ages of children taken from 1900, 1910, and 1920 US Federal Census.

[26] “Just a Joke,” 22 September 1893, Birmingham News, P.3.

[27] 23 September 1893, Birmingham News, P.3., “Not the Man,” 24 September 1893, Birmingham Post-Herald, P.6.

[28] “It was sentence day,” 1 October 1893, Birmingham Post-Herald, P.1.

[29] “To Serve Sentences,” 1 November 1893, Birmingham Post-Herald, P.3.

[30] Year: 1900; Census Place: Chandler, Etowah, Alabama; Roll: 16; Page: 14; Enumeration District: 0158

[31] Year: 1910; Census Place: Chandler, Etowah, Alabama; Roll: T624_13; Page: 17a; Enumeration District: 0068; FHL microfilm: 1374026

[32] Year: 1920; Census Place: Chandler, Etowah, Alabama; Roll: T625_15; Page: 7B; Enumeration District: 106

[33] Year: 1930; Census Place: Hoppers, Etowah, Alabama; Page: 2A; Enumeration District: 0036; FHL microfilm: 2339751

Be First to Comment